Coast Guard Life Saving Station

This is the twelth post in a multi-part series on the Municipal Bridge Vision.

After posting our research regarding the Municipal Bridge Vision and the 1928-1929 construction period, we received a number of comments about possible fulfillments of this vision in 1936-1938. We had already done some research on this and were preparing to present our findings when one reader made us aware of the existence of the official log books of the Coast Guard Life Saving Station #10 in Louisville at the National Archives. This reader was insistent that these log books would point to a construction event related to the bridge in 1936 and would contain documented evidence of sixteen men falling to their deaths. At first, we were quite skeptical of his claims and questioned whether or not these logs would be of any value to our search. However, we want to be as thorough as we can so we decided to take a little time and check it out before continuing to publish our information on 1936-1938.

We’re glad we did.

Life Saving Station #10

First, a little background of Life Saving Station #10 at Louisville, KY is in order. In service from 1881 until 1972, this station was placed near the falls of the Ohio because it was the most dangerous section of the river. The station was manned around the clock and operated as a bonafide Coast Guard Station. Over the years, there were three different vessels that served as the Life Saving Station. The last vessel was put into service in 1929 and was originally named The Louisville. When the vessel was retired in 1972 it was renamed to The Mayor Andrew Broaddus. It is now listed on the National Register of Historic Places and you can still visit it today.

The Log Books

We contacted the National Archives at Atlanta and discussed these log books with the archivists. The NARA staff were extremely helpful during our search. They were able to describe in general what sort of information was contained in the logs. They contain daily records from the station, including records of every rescue and recovery operation that the Coast Guard participated in. Since the station was located less than a half mile from the bridge, the Coast Guard would be the first responders to any event on the bridge where someone fell into the river. We decided to take a trip to examine these logs. The sheer volume of what was available was quite overwhelming and we had to develop a strategy to examine them in detail while making the most of our time at the archives. We decided it would be best to photograph the log books so we could enlist the help of others in examining them. It took us a few weeks to figure out the most reasonable way to accomplish this and arrange travel.

The Experience

The log books are available for public examination under pretty serious security. Entering the building requires a photo ID, a trip through a metal detector and having your belongings x-rayed. Any equipment you bring into the facility (laptops, camera, etc) requires a pass and recording of serial numbers. These items are generally inspected when you leave the facility. There are several different types of items at the archives, but if you want to review original historic documents you have to do so in a specific area. This area is secured by badge readers. When you enter, you must present a NARA issued researcher identification card. If you don’t have one, you must register and obtain one on-site. You have to go through a training presentation on handling the documents you are about to examine. Once you’ve completed this, you can set up your work area under the supervision of an archivist. Jackets, backpacks, and other bags are not allowed in the room once you are set up. The archivist delivers your materials to you with a chain of custody form. You are monitored by a person and security cameras while in the examination area.

Photographing the Log Books

While at the archives, we photographed all of the log books from May 1, 1928 through December 31, 1939. Here’s the setup we used to photograph these logs:

The pictures were taken using a Nikon D5100 mounted on a Manfrotto tripod. An LED light prevented shadowing. Using a remote shutter release, we simply aligned the log under the camera and took photographs as we turned to each page. Small bag weights were used to hold pages open. All images were shot at 16 Megapixels and captured in RAW and JPEG formats. Over 100GB of images were generated. Even using this setup, we spent 16 hours over two days photographing these books. Why? In the interest of full disclosure, we’re going to share all of them with you so you can examine them yourself if you wish. Right now we’re in the process of cropping the images and will be posting them online as jpegs of a reasonable size and detail.

Log Pages

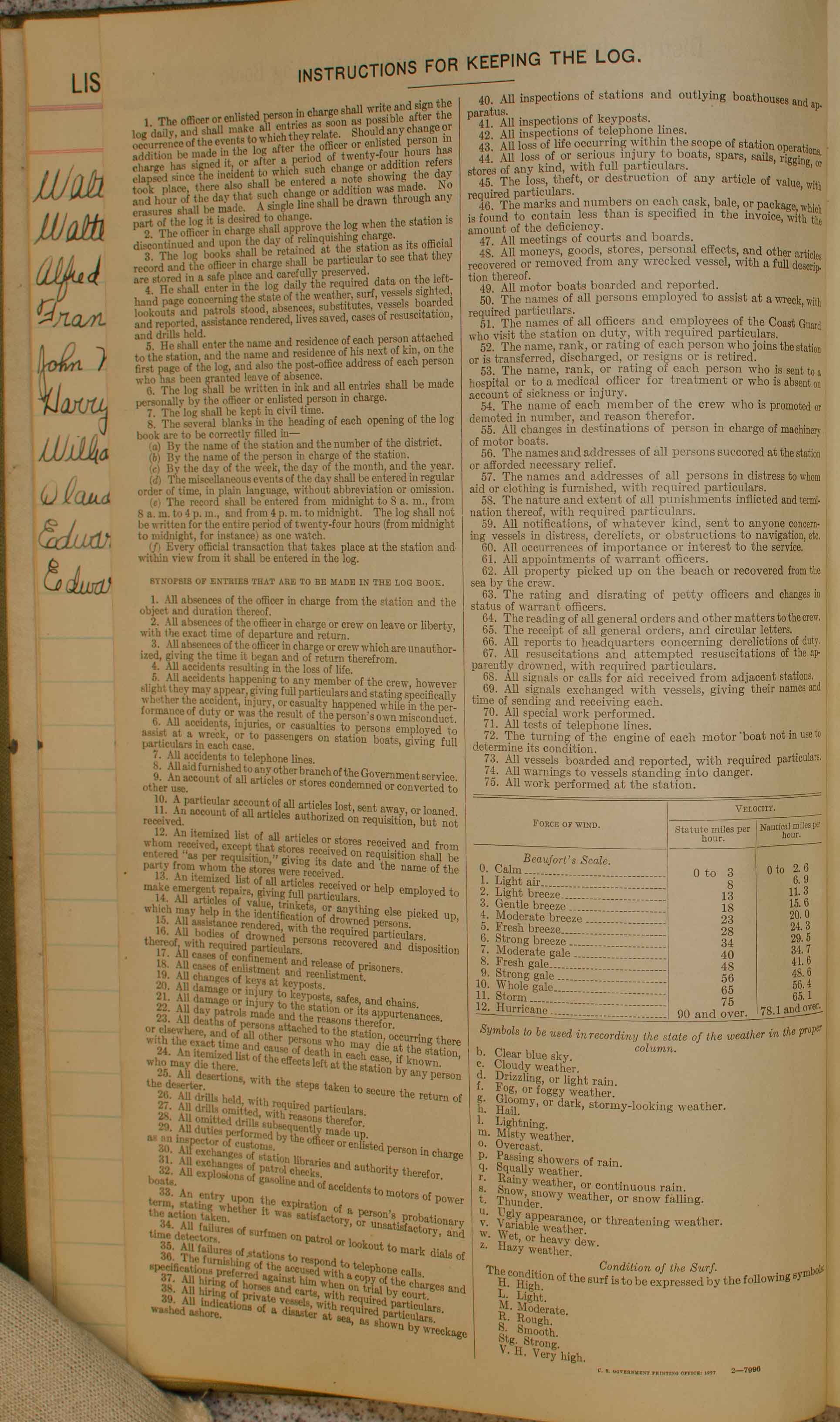

Each day the log contained the wind direction, force, barometric pressure, temperature, and surf conditions. These all had to be recorded at 4 AM, 8 AM, Noon, 4 PM, 8 PM, and Midnight. The log also records the number and types of ships that passed. It appears that the main types tracked were steamers and barges in tow. The station ran a regular lookout schedule which was recorded every two hours. Absences for vacation or sick leave were recorded. The log includes any drills held as well as a count of vessel boardings, inspections, and most importantly, the cases of assistance and number of lives saved. Finally, the second page of the daily log included a record of miscellaneous events of the day, recorded in chronological order. The log was signed by the officer in charge at the end of each day. Each log book starts with explicit instructions on how the log must be filled out:

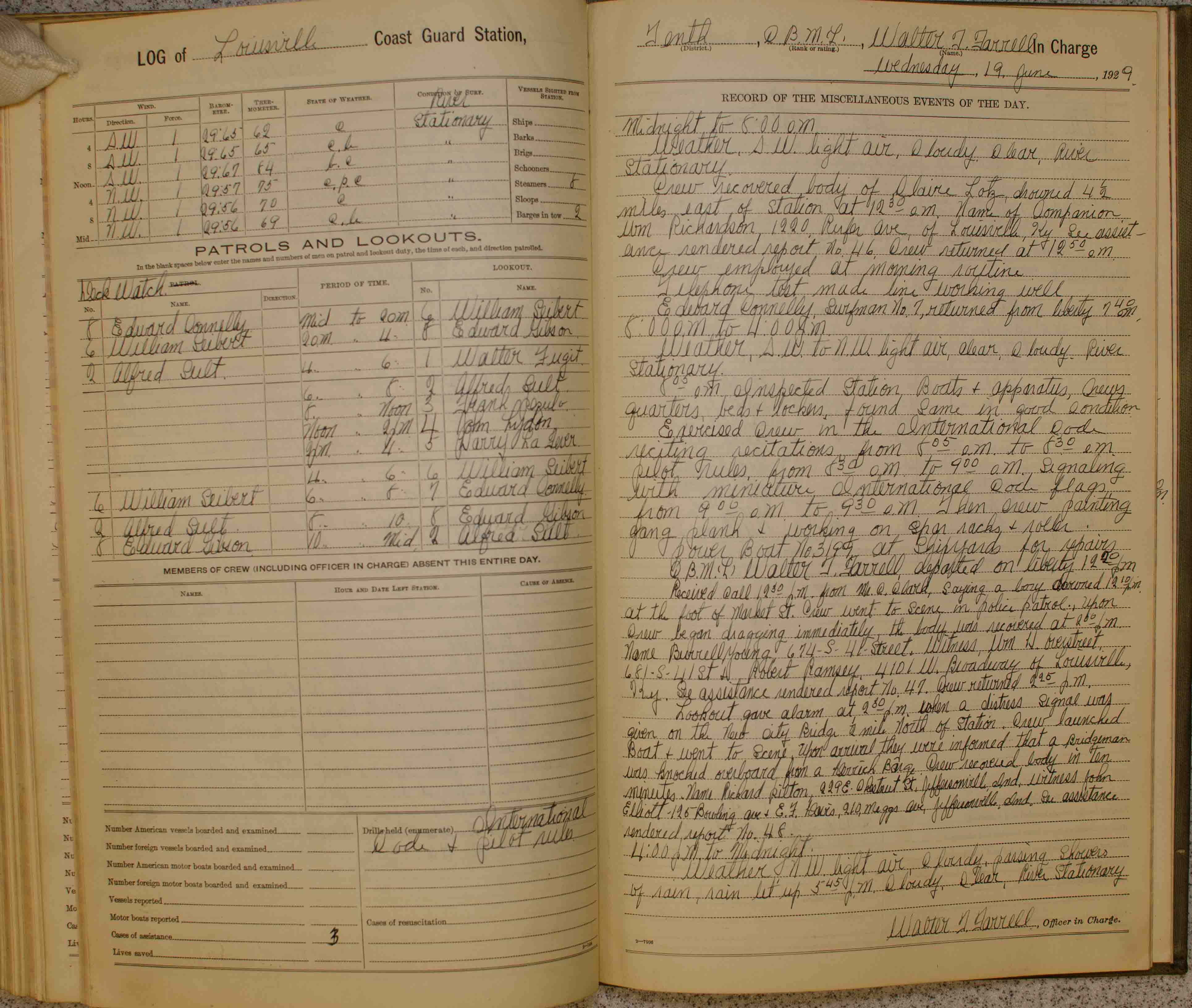

Here’s a sample log page from June 19, 1929. This is the day Richard Pilton was hit by an iron crank in the temple and was knocked off the bridge. The report in the Coast Guard log book matches the newspaper stories we published previously on this blog.

If you’re having trouble viewing this log page you can view it full size using this link.

The second bridge death we previously reported does not appear in the Coast Guard log because the man who died did not fall into the water and the Coast Guard was not part of the recovery operation.

Summary

With some help from one of our readers, we’ve discovered additional contemporary official government records that can be used to validate our findings from 1928 - 1929 during the construction of the municipal bridge. Further, these records can be used to determine if indeed sixteen men fell to their deaths and drowned in the Ohio River after the construction of the municipal bridge. We’re working on getting these images processed and will be posting them here and on our Facebook Page once we have them complete. Stay tuned.

blog comments powered by Disqus