The Modjeski and Masters Report - Part 2

This is the ninth post in a multi-part series on the Municipal Bridge Vision.

Early on in our research we learned of the existence of an official engineering report on the building of the Municipal Bridge. This report was delivered to the Louisville Bridge Commission in 1930 and contains many details about the bridge’s construction that are of interest to our search. We’ve already discussed the first half of the report. In this post, we’ll take a look at what’s in the second half of the engineer’s report.

Appendices A and B

Appendix A lists all of the personnel involved in the bridge project including the members of the various iterations of the commission, the consulting engineers, the architect, the office staff, the field staff, and the mill and shop inspection staff.

Appendix B lists the dimensions and quantities associated with the bridge construction. This includes things like the length of the bridge, the depth of the deepest foundation, the weight of the superstructure, as well as the quantities of limestone and granite used. This section also includes the amount of steel and the yardage of concrete used in construction.

Appendix C: Statement of Costs

This section is basically an accounting of the bridge construction costs. This appendix is very relevant to our search because it represents the actual costs associated with the bridge and was issued in the year after the construction was complete. The statement of costs is very detailed, going so far as to document the $190.25 that was spent on postage.

We can compare the actual costs with the contracted costs reported in a few newspaper articles before and during the construction to see if there are any significant cost over-runs. A large accident with a collapsing span would have necessitated the purchase of additional materials and significantly increased the labor cost which would likely show up as a cost over-run.

The original budget for the bridge was $5,000,000 and this was the amount of the bonds issued. According to an article in the Jefferesonville Evening News on June 9, 1928, this sum of money was to be delivered to the bridge commission on June 20, 1928. Appendix C of this report lists the grand total cost of the bridge as $4,821,087.75. The bridge was completed under budget.

The contract for building the superstructure of the bridge was signed in July, 1928. According to an article in the Jeffersonville Evening News on July 20, 1928 the bid was for $1,915,066. Remember, this was for the superstructure, the most likely portion of the bridge to actually collapse. The statement of costs lists the actual cost of this portion of the construction as $1,792,378.92. There were no cost over-runs in this portion of the construction, in fact, this portion of the construction came in over 6% under budget.

Another article in the Jeffersonville Evening News on December 20, 1928 mentions that the Bridge Commission was granted a building permit for the administration building and toll houses valued at $150,000. The statement of costs lists this work as being completed for $133,099.55.

Appendix D: Specifications

The next section of the report includes specifications for the materials that were used in the construction of the bridge. These specifications are very detailed. The first six pages of this appendix are dedicated to the concrete and stone/masonry to be used in the construction. These specifications include the tests to be used on materials. The tests are not arbitrary, but rather, reference specific test methods outlined by The American Society for Testing Materials. (ASTM) Each lot of cement was to be tested and the engineers state that “each lot shall show practically uniform results in tests; marked deviation from such results will be considered cause for rejection, even though test requirements may otherwise be fulfilled.” We can see from this statement that the engineers were very concerned about the quality of materials to be used in the bridge. The thoroughness and preciseness of this section of the document bear further witness to this.

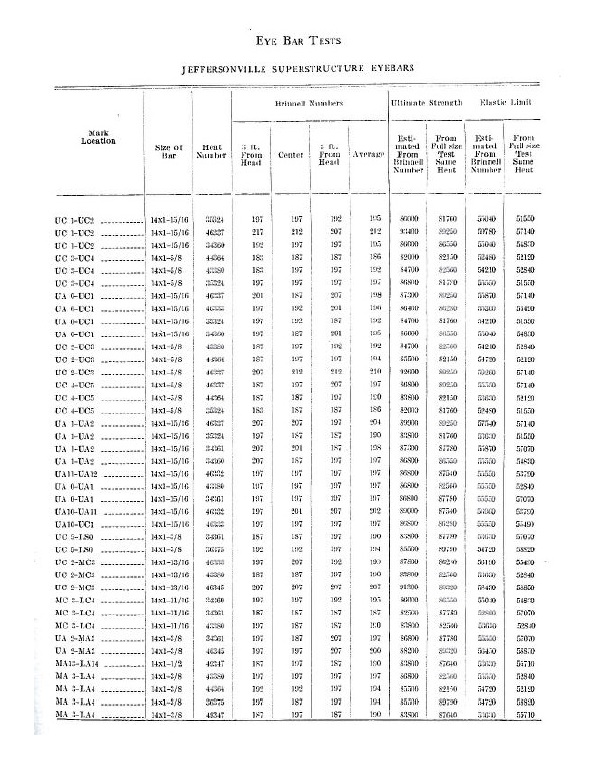

This appendix goes on to state the specifications for the steel used in the bridge for the next five pages. This section is also very detailed and includes references to industry specifications created by The American Railway Engineering Association. Every finished piece of steel was required to be stamped with it’s melt number. The tests for the steel where required to be furnished from the manufacturer’s chief chemist. The [eyebars] (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eyebar) were required to have an ultimate strength of at least 80,000 pounds per square inch. Manufacturers were required to use accurate pyrometers in the furnaces and open these records for inspection by the bridge engineers so they could audit the process to make sure the heat treating process was being performed correctly.

Appendices E1-E4

The remaining ten pages of the engineers’ report was dedicated to four appendices that included the actual test results for the materials specified in Appendix D:

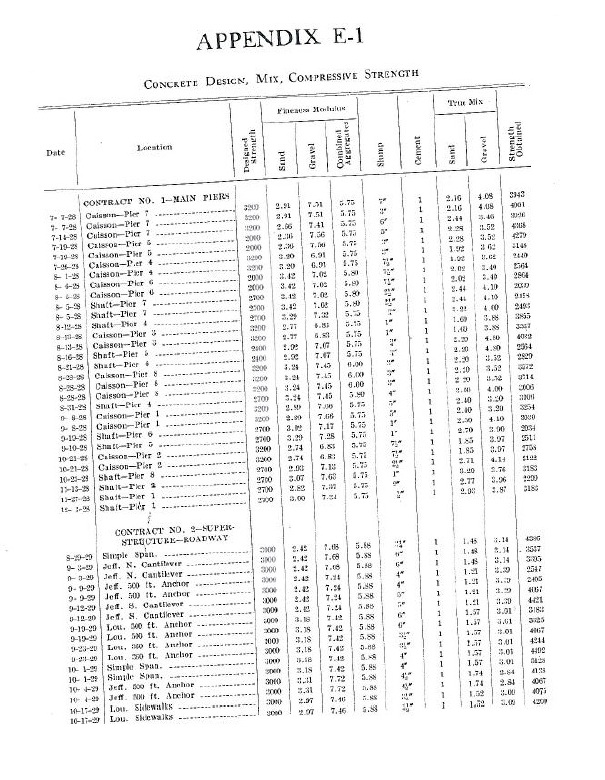

- Appendix E-1 is a table of the concrete tests by date and location.

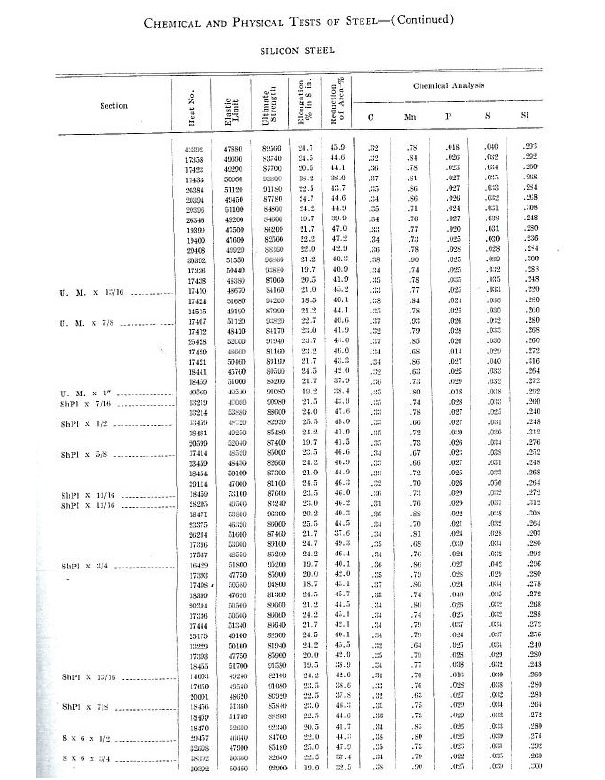

- Appendix E-2 is a table listing the detailed chemical and physical test results of the silicon steel used in the construction listed by section and heat number.

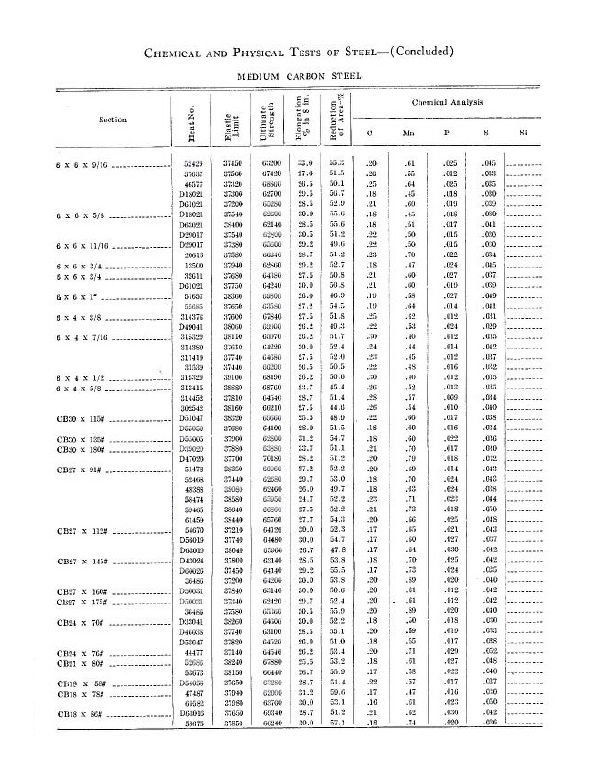

- Appendix E-3 is a table of the detailed chemical and physical tests results of the medium carbon steel used in the construction listed by section and heat number.

- Appendix E-4 is a table of the tests results of the eye bars used in the construction. These tests are listed by mark location, size, and melt number.

Summary Of Modjeski and Masters Report

The engineer’s report states there were some challenges associated with constructing the bridge piers, but indicates that the remainder of the construction was completed normally. There are no mentions of collapsing cranes or spans, and no records of any major failures or catastrophic accidents. This bridge was erected with less stress on the structure than there would have been using a more traditional bridge construction process. There was less weight on the superstructure during construction than normal, and barges were under the bridge sections that were being worked on. Safety is mentioned in the report. The statement of costs does not appear to show any additional unplanned costs that would be associated with a major accident or collapse. The specifications for the materials to be used in the bridge are very specific and require industry standard tests to be performed. The report includes the documented test results for these materials and, to our untrained eyes, there appears to be no significant defects documented in these test results.

blog comments powered by Disqus