And There, Friends, Is Where My Sorrow Started

If you are in the message, there’s no doubt that you are familiar with Brother Branham’s life story. It really is a riveting testimony and most people can identify, or at least empathize with, some of the hardship that touched Brother Branham’s early life. However, one portion of Brother Branham’s life story always stuck out to us as being particularly tragic: the events leading up to Hope and Sharon Rose’s deaths.

You probably recall the story of Brother Branham travelling through northern Indiana on his way back from Michigan and stumbling across a large Pentecostal gathering. At this time, Brother Branham was a Missionary Baptist and was unfamiliar with the Pentecostal people. Intrigued, he stopped and attended the meeting. Brother Branham slept in a corn field and attended a service the next morning where he was asked to give an impromptu sermon. After his sermon, Brother Branham received many invitations to come hold revivals at a number of churches.

When he returned home excited to go out and preach amongst the Pentecostal people, Brother Branham was rebuffed by his mother-in-law:

And–and there, friends, is where my sorrows started. I listened to my mother-in-law in the stead of God. He was giving me the opportunity. And there this gift would’ve been manifested long time ago, if I’d just went ahead and done what God told me to do.

But instead of that, I didn’t want her to be angry, and I didn’t want to hurt nobody’s feelings. And so I just–just let it go like that. Just walked, I just said, “All right, we won’t go.”

And right there, the sorrows started. Immediately after that, my father died. My brother was killed a few nights later from that. I almost lost my own… I lost my father, my brother, my wife, my baby, and my sister-in-law, and almost my own life within about six month’s time. And just started going down. My church, pretty near everything went down, down, down. Hope taken sick.

Life Story, Phoenix, AZ April 15, 1951

When Hope was on her death bed, Hope and Brother Branham talked about what a mistake it had been for them to not accept the invitations to go out amongst the Pentecostals. It was a terrible price to pay for his disobedience.

The following account in Brother Branham's own words, is from Life Story, preached on July 20, 1952 in Hammond, Indiana:

And when God brought us the little boy, how happy we were together. Went on, and life went on. After while John Ryan, back there come into my life. I met him. He asked me to come to Dowagiac one day where--where he lives over in Dowagiac, Michigan, to go on a little vacation. We saved our money and everything. And I had about, oh, maybe ten or twelve dollars saved up.

I'm fixing to come to the end of the story, now, just in a little bit. I'm, know I'm holding you, it's just I got about ten, twelve more minutes to be out on time. But we come to Dowagiac. I've tried to hold myself up and hit the high spots now. Now pray for me.

When I went to Dowagiac with Brother Ryan back there, I went to his home, a little humble home about like I lived in. His wife, but she would swear by him. He had a fine boy. And so they made me very welcome. And on my road back home, going back home, I come through Mishawaka. And I looked out there, and there was a groups of people swarmed out there, and cars, and Cadillacs, and Fords, and cops trying to keep order around. I thought, "What's going on here?" And I hear the singing, you know, and going on. My, everybody screaming and hollering. I thought, "Well, is it a funeral, or what's going on?"

It was at a church house. And I stops and goes in. Come to find out, it was a convention where there was a group of the Pentecostal people, was holding a convention over there. And they had to hold it in the north, because of the race conditions they couldn't hold it, and it was a international convention. They was holding it in a big tabernacle at Mishawaka.

So I--I never seen the Pentecost before, so I thought, "Well, believe I'll go and see what it looks like." So I walked in, and there they was all clapping their hands [Brother Branham claps his hands--Ed.] like that, and screaming and singing. I thought, "What manners. Tsk, tsk, tsk, tsk, tsk, never seen anything like that in my life. What are they all talking about?"

And here was a colored man up there, and he was singing. And he was singing:

I know it was the Blood, And all the congregation: I know it was the Blood.

And here he'd run down through there and grab somebody up and hug them like that, white, colored and all, said:

I know it was the Blood for me;

One day when I was lost, He died upon the Cross,

I know it was the Blood for me...

Running up and down the aisle. And I thought, "I never seen anything like that in my life." And how... I said that... And somebody jump up and scream and speak in tongues, and I thought, "Say, what is this, anyhow?"

And then a preacher got up there, and he got to preaching about the baptism of the Holy Ghost. And it looked like that his finger was about that long, and he pointed me out right back in the back. He was talking to me. And I thought, "Say, how'd that guy know anything about me?" See? And oh, there was hundreds and oh, it was thous-... two or three thousand, I guess, in the... all together in the meeting.

And some group from up here at Chicago, colored group, they come up, called Locust Grove, or Piney Wood, or something like that, a quartet that... I never heard such singing in my life. Well, I thought, "There's one thing you have to say about them people, they're not ashamed of their religion. That's one thing sure. They're--they're not ashamed of it."

So I thought, "You know, I believe I'll come back tonight." And I went out and counted my money. I had just enough to get enough gasoline to come back, and twenty cents left. Well, I knowed how much gasoline it'd take. Now I couldn't get a tourist court, so I thought, "I'll sleep out there in a cornfield." So I went down and got me twenty cents worth of stale rolls. And I thought, "I can live on them for a couple days, but I want to find out what this is all about." So I went out and got my rolls and put them in the back of my car, and--and went over.

Then that night, he said, "I want all ministers," the--the spokesman said, "I want all ministers come to the platform." There was just about, I guess about a two or three hundred of them at the platform. They were all (white, colored, and all) setting on the platform. He said, "Now, we haven't got time for you to preach, we just want you to come right down the row, and just say who you are, where you are from."

When it come my place, I said, "Evangelist, William Branham, Jeffersonville, Indiana," set down. Next, next, next, on like that.

Come to find out, I was the youngest man was there. I was twenty-three years old then, the youngest man at the--at the platform. I didn't know it at that time. The next morning...

Well, then we went on that night. And I want to tell you what happened that night. I set, heard all them ministers preaching that day about, oh, the Deity of Christ, and the great messages about His walk on life, and His sacrifice, and so forth, and on the different things.

But that night they brought an old colored man out, just a little bit of rim of white hair around the back of his head here, great big, long, felt preacher's coat on, one of the old-fashion, long frock-tail coats with a velvet collar. Poor old fellow walked out there like this. I thought, "That poor old man. Isn't that a shame?" I said, "Poor old Dad." I said, "I guess he's preached a long time." And he stood there.

And I never seen a microphone before. I was a country preacher. So they had the microphones hanging up. It was something new then, you know.

So this old fellow got before there, he said, "Deah child'en." Uh-oh. He said, "I's gwine to take my text tonight from back in--in Job." Said, "Wheah was you when I laid the foundation of the world? Declare unto me wheah these, they're fastened to, so when the mo'ning stars sing together and the sons of God shouted for joy."

I thought, "That poor old fellow, his preaching days are about finished. He's old." See? Instead of coming down on the earth with it, like this, brother, he went back yonder about ten million years before the foundation of the world was ever laid; he climbed up into the skies; and he preached about what went on in the skies, the sons of God shouting for joy. He come on down through the dispensations and brought Him back on the horizontal rainbow, back here, back over in the Millennium.

And--and about that time he got all happy, and when he did, he went, "Whoopee," jumped up in the air, clicked his heels together, said, "Glory to God," said, "Hallelujah, there's not enough room here for me to preach." And off the platform he walked like that, like a kid.

I said, "Brother, if it'll make an old man act like that, what would it do for me? I want that. That's what I want. That's what my heart hungers for, if it'll make an old man act like that. I want..." That's what I wanted. I said, "Oh, my, them people's got something."

That night I went out in the cornfield, I thought, "I better press my trousers." So I took the two seats of my old Ford, and put them together, laid my trousers back and forth like this, and put the seats down to press them, laid down in some grass over at the side of the field out here somewhere in Indiana, out here.

And I laid there under that little old cherry tree that night, and I prayed, "God, somehow or another, give me favor with them people. That's what I want. **Baptist or no Baptist**, that's what I want. That's what my hungry heart's feeling for. That's what it's reaching for. There's the people that I've wanted to see all my life."

Next morning, I went down. Nobody knowed me, you know, so I put on my little old seersucker trousers, and put a T-shirt on. Nobody knowed I was a preacher, so I went down, and I set down. And when I set down, here come a colored brother up and set down beside of me; and over here set a lady. And I--I set down there.

And so they got up that morning just playing the music and everything. And there was a brother, his daughter come out and played a trumpet, Whitherspoon, I believe was his name. And he... That girl played the most beautiful Blue Galilee that I--I sat there and cried like a baby. And I was setting there.

Then up to the platform come a minister by the name of Kurtz. He said, "Last night at the platform, the youngest minister we had here was an evangelist by the name of William Branham," said, "from Jeffersonville, Indiana." Said, "We want him to speak this morning."

Oh, my. "My congregation," I thought, "in seersucker trousers and a T-shirt." So I just hunkered down real low like this, you know.

In a few minutes, he waited a few minutes, he got to the microphone again, he said, "If there's anybody here knows where William Branham from Jeffersonville, an evangelist, was on the platform last night, we want him, this morning, to bring the message this morning. Tell him to come to the platform."

I scooted down real low, you know, like way down low. I thought, "Seersucker trousers, you know, and T-shirt." So I got real low. And I didn't want to get up before them people, anyhow. They had something that I didn't know nothing about. So I just set real still.

Directly that colored man looked around me, said, "Say, you know him?"

Uh-oh. Something had to happen. And I didn't... I knowed... I didn't want to lie to the man. I said, "Look, fellow. Listen, I want to tell you something." I said, "I'm he. See?"

He said, "I thought you getting down there kind of low about something."

And I said, "Well, look," I said, "are you a minister?"

He said, "Yah, suh." I said...

He said, "Go on up there, fella."

And I said, "No--no, look, look, look." I said, "I want to tell you something." I said, "I--I--I've got on these seersucker trousers and this T-shirt," I said, "I don't want to get up there."

Said, "Them people don't care what you dress like, man. Get on up theah."

And I said, "No--no, thank you, sir."

And somebody said, "Has anybody ever found Reverend Branham?"

He said, "Here he is. Here he is." Hmm. "Here he is."

Oh, my. I got up, and my ears red, you know. And I had my Bible under my arm, and I walked up to the platform kind of sheepish-looking, you know, and scared to death. I walked up. I thought, "Oh, my. Last night I was praying all night to give me favor, now if God's going to let me get up before them; if I ain't going to get up, then how I'm going to get favor?"

So I got up, I said... well, not a thing on my mind; I was scared and trembling. I never... didn't know how close to stand to that little old microphone hanging with a string, hanging down like that. I didn't know how to stand by that. And all this great big tabernacle, you know, and I said, "Well, folks," I said, "I--I don't know very much about the--the way you preach and things." I said, "I just... I was coming up the road. And--and I didn't know..."

And I happened to turn over there to Luke to the rich man lifted up his eyes in hell, and he seen Lazarus far off, and then he cried. I took my text: And Then He Cried.

And I got--got to talking, and I said, "Then the rich man down in hell there was no church; then he cried." I said, "There was no children; then he cried. There were no songs; then he cried. There was no God; then he cried." And I got started, people got screaming; then I cried.

Away it went, and the first thing you know everybody on their feet, "then he cried, and then he cried." And the next thing I knew, I was out in the yard. Well, I don't know what happened. And everybody was blessing God and carrying on, the congregation screaming and shouting. I don't know what I done. I just lost myself somewhere.

First thing you know, up come a great big fellow from Texas, a big ten-gallon hat on and cowboy boots, walked up, said, "Say, are you a evangelist?"

I said, "Yes, sir."

He said, "How about coming down, Texas, and holding me a revival?"

I said, "Well, are you a preacher?"

Said, "Sure." I looked at them big high-heel boots, and that great big cowboy hat, I thought, "Maybe it doesn't make any difference the way..."

Next thing, a fellow walked up had on little golf pants like this. He said, "Say," he said, "I'm from Florida." He said, "I have so-many saints down there at a church, or somewhere." Said, "I'd like for you to hold..."

I said, "Are you a preacher?"

He said, "Yes, sir."

I thought, "Well, my seersucker trousers and T-shirt ain't so much out of line after all around this place around here." So I begin to look at it. And we had a clerical coat and collar, and everything we wore, you know. So they... I thought, "Well, that's all right."

So then a woman stepped up from up around somewhere way up in the northern part of Michigan. She was with the Indians. She said, "I just know, while you was preaching, the Lord told me that you should come and help me up there with the Indian."

I said, "Just a minute. Let me get a piece of paper." And I went to writing down these names and addresses. And my, I had a string of them that long, last me a year. My, was I happy. Out of there I went, and jumped in my old Ford, and down the road we went to Jeffersonville as hard as we could go, sixty miles an hour: thirty this way and thirty up-and-down that way; just as hard as we could go, right down the road flying as hard as we could to go to Jeffersonville.

I jumped out of the car. As my wife, always, she come and run to meet me. And she said, "What you so happy about?"

I said, "Honey, you just don't realize." I said, "I met the happiest people in the world."

Said, "Well, where they at?"

I told her all about them. And I said, "Looky here. Let me show you something. You wouldn't believe that this preacher boyfriend of yours, looky here: All them people asked me, this whole line, down through Texas, Louisiana, and everywhere, come preach for them. See there?" I said, "I prayed all night under a cherry tree out there, and God told me..."

Said, "What kind of... what do they act like?"

I said, "Oh, don't ask me." I said, "They just act any way."

And so she said, "Oh, my," said... She said...

I said, "And they asked me to go. I'm going to quit my job and go to preaching right out with them, leave my church."

She said, "Well..."

I said, "Will you go with me?"

God bless her heart. She said, "I promised to go with you anywhere, and I will go anywhere that you go." That's a real wife. She's in her grave today, but still I'm glad that I can say this, and her son, her and my son, standing, listening. His mother was a queen.

And I--I said, "Well, look," I said, "We..." I said, "We'll tell our parents."

I went and told Mama. I said, "Mama, looky here." And I told her about people.

She said, "You know what?" Said, "Billy, a long time ago, down in Kentucky, we had what they all called the old Lone Star Baptist." Hmm. Said, "And they used to shout and scream, and carry on like that." She said, "That's real heartfelt religion."

I said, "That's what I've believed in all my life." And I said, "You ought to see them."

She said, "Well, the... I trust that God will bless you, Bill."

And I said, "All right." So we went to tell her mother, then.

And during this time, her mother and father had separated. And I said... We went to tell her mother. And I said, "Mrs.--Mrs. Brumbach," I said, "I--I have found the wonderful people," like that.

And she was setting on the porch, you know. Now, don't get mad at me if you're here, Mrs. Brumbach. So she said... She was setting on the porch fanning. She said, "William, I will give you to understand, I will never give my daughter permission to go out with a bunch of holy-rollers like that." Oh, my. She said, "That bunch of trash," said, "She'd never have a decent dress to put on her back."

I said, "Well, Mrs. Brumbach, it isn't a dress proposition." I said, "The thing of it is, is I feel that God wants me to do it."

And she said, "Look, why don't you go up there at the church where you got a congregation coming, and think about getting yourself a parsonage and a place to take your wife and baby to, and instead of pulling her out: today she's got something to eat, and tomorrow she's got nothing, and things like this." She said, "Never indeed, will I ever permit my daughter to go like that. And if she does go, her mother will go to a grave brokenhearted."

And Hope said, "Mama, you mean that?"

And she said, "That's just what I mean." That settled it.

Hope started crying. I put my arm around her and walked away. I said, "But Mrs. Brumbach, she's my wife."

She said, "But she's my daughter."

I said, "Yes, ma'am."

I walked away, went down. She looked at me, Hope did. She said, "Bill, that's my mother, but I will go with you." See? I said... God bless her heart. She said, "I will go with you."

And I said, "Honey, I..." I said, "I guess I'm carrying water on both shoulders." But I said, "I don't want to hurt her feelings." She said... I said, "What if something would happen to her and then you'd be worried all your life you--you broke your mother's heart." I said, "Maybe we'll just put it off a little while."

And friends, there's where I made the worst step I ever made in my life, right there. We put it off.

About few weeks after that, things begin to happen. The flood come on later from that. And the first thing you know, wife got sick, Billy got sick; during that wrong. Right after that, the little girl... Just eleven months difference between Billy and his little--his little sister, which was Sharon Rose.

I wanted to name her a Bible name. So I couldn't call her the Rose of Sharon, so I called her Sharon Rose; and I--I named her that. She was a darling lovely little thing. And the first thing you know, the flood came up. She was laying there with pneumonia. And our doctor, Dr. Sam Adair came. And he's a brother to me. He looked at her, he said, "Bill, she's seriously ill." Said, "Don't you go to bed." Right at Christmas time. He said, "Don't you go to bed tonight. You give her orange juice all night long. Make her drink at least two gallons tonight to break that fever. She's got a fever of hundred and five," and said, "You must break that fever right away."

I said, "All right." And I set up and give her orange juice all night. The next morning the fever was a little lower. So her mother came up. And she just didn't like Dr. Adair at all. She liked another doctor there in the city. And she said, "I'm going to take her down home. This house is not--not equipped with heat and stuff for her to stay." I said, "Well, I'd rather ask Dr. Adair if we should move her." She said, "He ain't even got sense enough to know how to come in out of the rain." She said, "I wouldn't ask him nothing." She said, "I will get a doctor, a doctor..." I said, "But look, we shouldn't... we--we... I don't..."

And I called Dr. Adair. He said, "Bill, don't you move her." Said, "If you do, it'll kill her." Said, "Take her out in that cold, it's sub-zero weather right now, plumb down to that place, and change them rooms where..." Said, "Don't you do that." But 'course, there it was. And then I called him, I said, "She is going to do it anyhow." He said, "Then I will get off the case, Bill. I love you as--as a brother, you know that, but I will have to leave the case and turn it over to Dr. Baldwin." And I said, "Well... I... Doc, you know where my feeling is." I said, "I..."

So I went down there and I knelt down and prayed. I went over to the church. When I started to pray, looked like a black sheet come moving down in front of me. I went over, I said, "I don't believe she'll ever come from the bed." And all of them said, "Oh, Billy, you just think..." I said, "The same thing that happened about that flood," I said, "is the same thing that is telling me about my wife." I said, "I don't believe she'll come from the bed." Said, "Oh, I believe it's your wife and you just... that's the way you feel about it." But oh, my, a little later on, I will never forget how that was. Oh, it went on for a little bit; she got worse, worse.

Finally the flood come up, and I was on a rescue party out there. I had a speedboat and I was trying to get people out. And I remember one night they'd took her--they took her to the hospital, then put her over here in--in a place at the government. And her and both babies were sick, horribly sick. And I will never forget that fatal night when the floodwalls broke through down there. I heard a scream way back over on Chestnut Street. And I had a speedboat, and I got out there and tried to get a mother out of there. Just as I picked her up, she fainted. I picked her up in my arms and put her in the boat about eleven o'clock, put the babies in there. And when I got her back to shore, she began to scream, "My baby! My baby!" She had a baby there about two years old, and I thought she meant she had another little baby out there in that place. And back I went to try to get the baby.

I tied my boat up the side of the pillar of the porch, and when I went up into the room to try to look around for the baby, I heard the house giving away below, and I run down real quick just in time to jump into the water and hold on to the end of my boat, and pull the... And it sub-zero, sleeting and snowing. And I pulled the rope like that and got in my boat. The waves caught it and swept me out into the middle of the current, out into the river. And I got back in there. And I--I couldn't get my boat started: the old chain, it will pull on the outboard motor, you--you know, the old-timers, where you had a whirl on the top of it. And I'd pull and pull, and I couldn't get the thing started. And there was the Ohio Falls roaring just below me. Oh, brother, a way of a transgressor is hard. Don't you never think that.

And I pulled and it wouldn't start. And I pulled again and it wouldn't start. And I tried, and I got down in the boat, I said, "God, it isn't but a few more jumps down here till I would sink beneath those falls there, where they were roaring and bubbling, miles of water stretching through there." I said, "I got a sick wife and two babies laying out there in the hospital." I said, "Please, dear God, start this motor." All I could think: "'I will never let my girl go out with a bunch of that trash.'" And I say this with all due respects to every church: I find out what she called "trash" is the cream of the crop. That's exactly right. That's exactly right.

And I was pulling on that, and that kept roaring in my ears. And I pulled again, and I... Just a few minutes, and it started. And I had to pull right back upstream and give it all the gas that it could. Finally, I landed down almost to New Albany, just whirling the edge of those falls. I got back in, and run back up to the hospital to see where my wife was, and the flood had done took the thing away. It was gone. Now, where was my wife? Where was my babies? Wet and cold, I run out there and I met Major Wheatley. I'd just... Brother Ryan had just left somewhere; I don't know where he had went. I think he went with Brother George and them on out. And I met Brother George, the last time I seen him in life, he put his arms around me, said, "Brother Billy, with all my heart..." He was a converted medium. And he said, "...all my heart, I love Jesus Christ. And if I never see you again, I will see you in the morning." I said, "God bless you, George," as he went on. He was trying to find Brother Ryan then, somewhere, 'cause he was in the city.

And then I tried to find Hope. I couldn't find her. Some of them said, "No, there was no one drowned in that group." Said, "They all got on a train, and went out to Charlestown." Well, I jumped in my car and started to Charlestown, when I did that creek back there had cut off about five miles of solid water down through there. Some of them said, "No, the train got halfway out there and just washed off the trestles out there. They all drowned out there off of that trestle." Said, "They went out on a cattle car." My wife (her father, one of the heads down there on the railroad), and her (his daughter) with double pneumonia, and two babies with pneumonia: laying in a cattle car, and sleet and rain blowing on the road to somewhere, and washed out in the water.

I tell you, brother, there's a whole lot; when God calls you to do anything, don't you let no one stand in your way. You keep God first. And I tried to find... I couldn't get a way, and got my speedboat, and tried to get out into... towards Charlestown. I couldn't even touch the waters; the whirl would swing me plumb back. And I thought I was a pretty good boatman. And I tried it after time, till it was almost breaking day; no success at all, there. It was gone. Then I was marooned, then, found myself on a little island sitting out there. For three or four days I set alone there, where they had to drop me something to eat. I had a long time to think over whether that was a bunch of trash or not, whether to mind some woman or to mind what God said. No matter who it was, you listen to what God has got to say.

And there, after while, after I got across the waters, it dropped enough, I went to see where my wife was. They told me she was in Charlestown. Got there, she wasn't there. And old Colonel Hay (just went to Glory recently), he put his arm around me, said, "Let's go down to the railroad station." When I went down there, brokenhearted, crying, I didn't know what to do. Oh, my, I thought, "Babies are probably laying, drifted off yonder somewhere in some brush pile. The wife may be laying down there, also." Oh, how I cried, and begged, and repented, and told God. Look, friends, I believe if I'd have went on right then, where I was mixing up with that bunch of people who believed in the Supernatural, the Angel of God would've come to me and revealed that thing, and it would've been thousands times thousands of more people in Glory because of it. See? That's the reason I go day and night, and everywhere, putting my whole strength, 'cause I've got to redeem the time. I've got to do it.

And so when I... Finally, someone come and got me, said, "No, they're not drowned, Billy. I know where they are at. They're at Columbus, Indiana in the Baptist church." And I... They taken me up there and I run down through that hall that night, screaming to the top of my voice. I didn't care who heard me, "Hope, Hope, where are you, honey?" way down through there. And all the refugees back there on little old cots, and blankets hanging up. And I happened to look way down there at the end, I seen a bony hand holding up like that. I rushed real quick, pair of boots on, fell down there, and throwed my hat off, looked down there, and there laid my sweetheart, dying. Her hand moving up, her jaw sunk back, about three weeks or more before I'd found her. Her eyes were way back.

I put my hand over on her. She said, "I know I look horrible, Bill." I said, "Honey, you look all right." She said, "Now, don't tell me that, honey." I said, "O God, have mercy." I said, "Where's the babies?" She said, "Mom and them has got them over there in the building." I said, "Is Billy alive?" Said, "Yes." I said, "Sharon alive?" Said, "Yes." I said, "Oh, thanks be to God." I said, "I heard from Mama, and Mama's alive. She's over at some other place." I said, "I heard by radio. But I couldn't hear from you nowhere." And I said, "Oh, honey." And she said... I said, "You..." And I felt somebody tap me on the shoulder, and I looked up. He was a very smart-looking man. He said, "Reverend Branham?" And I said, "Yes sir." ...?... And I walked over there. Said, "Aren't you a friend of Dr. Sam Adair?" And I said, "Yes."

He said, "Your wife, I'm informed to tell you, I'm the doctor here." He said, "I'm informed to tell you, your wife has galloping TB. She just has a few days to live." Said, "She's going to die." I said, "No, doc. No, no, that isn't so." He said, "Oh, yes, it is, Reverend Branham. It is so." I said, "It can't be, doctor. You mean she's..." He said. "Yes." And said, "You'll be a very lucky man if your children pull through." Said, "I'm tending to the children, also." And I said, "O God, have mercy." He said. "Now, don't break down before her." I said, "All right, sir. All right." I said, "Thank you very much. Where is Dr. Sam?" He said, "I don't know where he's at." And I said, "Thank you, doctor." And I said, "I--I'll... Let me go back to her," I said, "just to be with her as much as I can." I said, "I--I--I won't break down."

I walked back nervously. I looked at her, and those pretty black eyes setting way deep back there, and her hair and her forehead. Oh, I seen she was going. I looked over, and I said, "Hope, sweetheart, you--you look all right." And she said, "Oh, maybe God will have mercy and let me live, Bill." And I said, "I hope He does, sweetheart." And so, a few days, I got her out of there, got her down to Jeffersonville to the home. And she kept getting worse, and worse, worse and worse. The two children begin to get better, but she got worse. And after while...

Dr. Adair, he tried everything he could. He sent to Louisville to a specialist of TB, brought over, and he said, "Well, if you had a pneumothorax machine." I went and borrowed the money and got a pneumothorax machine, and we give her the treatments. When, you know what pneumothorax is: they collapse the lung, you know, like that. And I'd hold her poor hand and it would grip till they'd bore that hole in there, and pump out the lung. And then, if I had it to go over again, I'd never let her suffer like that. And so, trying, but they were working hard to save her life. Finally, took her out to the hospital for x-ray. Here it come, right on up that tuberculosis pneumonia was coming right up, filling up the lung. He said, "You just got a few days, Reverend Branham. There's nothing in the world can be done. She's going to die." I said, "Almighty God has called for her to answer."

Oh, how could I stand that? How could I believe? How could I do it? I looked down there, and there laid my little Sharon Rose, a little suckling baby, about eleven-months-old; here was little Billy Paul just about eighteen-months-old, little bitty fellow; and to them, without a mother; and me. Oh, what could I do? I just couldn't believe it, hardly. I walked the floor; I cried; I--I done everything. I tell you, brother, you better mind God when God speaks to you. You do what He tells you. And I walked back and forth, finally come the hour. I was out in the car and I heard them call me, that I must come to the hospital at once; my wife was dying, said she couldn't live any longer. I rushed to the hospital real quick, threw off my coat, run up the steps.

And when I did (I will never forget it.), little Dr. Adair, a fine little fellow, and he come walking down the room. We fished together; we hunt together; we slept together; we were bosom buddies. And he's--he's a specialist. And he come walking down the hall with his head down. And he happened to look, standing down there, and he seen me, and tears rolled down his cheeks, and he ducked off into a room. I run down the hall real quick, and pulled open the door; he put his arm around me, he said, "Billy, boy," patting me. [Brother Branham pats something--Ed.] I said, "What is it, doc?" He said, "I just can't tell you, Bill." Said, "Just go ahead out and let the nurse tell you." I said, "Come on, doctor. What is it?" He said, "She's gone." I said, "She isn't gone, doc." Said, "Yes, she's gone." I said, "Doc, go with me to the room, will you?"

He said, "Bill, I can't do that." He said, "Hope, how we... Why, we was just like my sister." He said, "I--I can't go in that room again." So just then the nurse come in. She said, "Reverend Branham, here's some medicine. I want you to take this." I said, "I don't want your medicine." And she said... I went out to the room. She said, "I'm going with you." I said, "No, let me go alone." I said, "Let me go in and see her." And I walked in. I said, "Is she gone?" Said, "I--I think she is." Said, "Dr. Adair left a few minutes ago, and said there was nothing more could be done, that she was gone."

So I opened the door, walked in. And I looked laying there, and she had her eyes closed, her mouth was open; her little body was drawed down to about a hundred pounds, less than that, oh, like this. And I put my hand over on her forehead; it was sticky-like. And I said, "Hope, sweetheart, will you answer me?" I said, "Do... Will you--will you answer me, honey?" I said, "Will you speak to me just one more time?" I said, "God, I know I been wrong, but if You'll just let her speak to me one more time. Will You, Lord? Please let her speak." And while I was praying, I looked. If I live to be a hundred years old, I will never forget that. Those big dark eyes opened up and she looked at me. She motioned for me to get down. I looked at her, I said, "Sweetheart, you're all right, aren't you?"

She said, "Why did you call me, Bill? Why did you call me?" I said, "What do you mean?" She said, "Oh, I was so easy." She'd been suffering so hard. And I said, "What do you mean, 'easy,' honey?" She said, "Well," she said, "Bill, you know I'm going, don't you?" And I said, "No." She said, "I am." And she said, "Bill, I don't mind it." Said, "You know why I'm going, don't you?" And I said, "No." She said, "Bill, you remember the day we went up to Mother, and that bunch of people, who...?" I said, "I know it, honey." She said, "We ought not to have did that." Oh, then grinding my heart.

Just then the nurse run in the door, said, "Reverend Branham, you better take this." She motioned to the nurse. She took me by the hand, she said, "Louise," we knew them all well. She said, "Louise," (Hale) she said, "I hope when you get married that you have a husband like mine." She said, "He's been so good to me." She said, "I hope..." And Louise, she--she just couldn't stand it. She set the medicine down and went out of the room. And I said, "Honey, are you going?" She said, "I was being taken home, Bill." Said, "There was Someone dressed in white standing on each side of me. And I was going down a big beautiful path." And said, "It was peaceful, and the big palm trees like an orient, and the big birds a flying from tree to tree." Said, "It was such a beautiful place."

You know what I think? I think God let her break into Paradise just as she was going over. And she said, "You know, Bill, that religion that you... we been talking about since we received the Holy Ghost?" And I said, "Yes." She said, "Don't never cease to preach that." She said, "Stay with that." She said, "That's the thing." And I said, "Honey, if I would've probably listened..." She said, "Yes, Bill." She said, "Now look, honey," she said, "I'm going fast." She said, "But remember, that wonderful Holy Spirit that we've received," she said, "It's taking me through." She said, "Promise me this, honey, that you'll never, never cease. You'll never let up; you'll always stand true to That." She said, "It's wonderful in death." And I said, "I--I will." She said, "I got a few things..." for me to promise. I said, "What is it, honey?"

She said, "You remember that time when we was in Louisville and you was going on that hunting trip, and you wanted to buy that little .22 rifle." I said, "Yes." And said, "You didn't even have enough (three dollars), to make the down payment?" I said, "Yes." I'm very fond of rifles and things; it's a--a sport to me, and a recreation, I should say. And I--I said, "I remember that."

She said, "Honey, I've tried my best to save our nickels and things to get it for you." She said, "After I'm gone, and you go home, and right on the top of that old folding bed" (where Brother Ryan slept), she said, "right up on top there, under the newspaper, you'll find the money that I've saved." Said, "I've took that out of allowance for my clothes and things that you'd let me have," she said, "to save it so I could get enough for a down payment to get you that rifle." You'll never know how I felt when I looked under there and seen two dollars and seventy cents in nickels and dimes to buy the rifle.

She said, "And another thing." She told me about some stockings that I'd bought her one time that... I didn't know how to buy stockings, and I called it socks, and I got the wrong kind. And she told me that it was the wrong kind, and she'd give them to my mother because it wasn't the kind of... that she wore. And she said, "Another thing, I want you to promise me." Said, "What's that?" She said, "That you won't live single." And I said, "Oh, Hope, don't, please. Please don't ask me, honey." She said, "Look Bill," she said, "in Heaven there'll be no marriage or given in marriage." She said, "And I got two little babies here I'm leaving you with." And she said, "I don't mind going, but I hate to leave you." Said, "I hate to leave Billy Paul and Sharon." She said, "But Billy, if--if they're raised up, and you in the ministry, and they be pulled about from pillar to post," she said, "find some good girl, some good girl that's got the Holy Ghost," said, "let her be in my place as a mother."

I thought of a twenty-two-year-old woman, going like that. I couldn't promise her. I said, "Honey, I--I--I just can't promise that. I--I--I can't do it." She said, "You wouldn't let me go unhappy?" I said, "No." I said, "I will just do the best I can." She said, "Bill, I... They're coming back." Said, "Don't think I'm beside myself; I'm not," she said, "but I feel them coming near. They're coming after me." I stepped back, looked at her, I said, "Sweetheart, if you are going, all right. I'll take your body out here on Walnut Ridge graveyard, and I'll make a mound, and I'll put you in there." And I said, "Then if Jesus comes before I go, I'll be somewhere on the battlefield preaching the Holy Ghost Gospel." And I said, "If I sleep, I'll be by your side." And I said, "Look, honey, for my last date with you, my sweetheart," I said, "when the great pearly white City comes lowering down from God out of Heaven, and the moon and sun stand there together, black, dripping with blood..."

We don't believe in death of Christians. You can't prove to me that a Christian dies. The Blood of Jesus Christ takes away sin; it doesn't cover it. The believer goes in the Presence of God now. And I said, "Honey, if I'm asleep that day; if--if I'm awake, you'll come first, for they which are dead in Christ shall rise first." I said, "You run quickly up to the side of the City gate." And I said, "When you see Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, and them coming," I said, "you start screaming your... my name, to the top of your voice, 'Bill, Bill,' as loud as you can." And I said, "I'll get Sharon and Billy and get them together, and I'll meet you there at the gate before we go in." She took hold of my hand; she squeezed it. I raised down, and kissed her good-bye. Them angel eyes looked up at me again as she was taken away, she said, "I'll be waiting for you at the gate." God took her precious soul to Glory. There I stood, looking down. What could I do? My sweetheart gone, the very part of my heart pulled away. I went out of there to go home; took her body down to the undertaker's establishment; she was embalmed. And I went home, tried to go to sleep; I couldn't do it. And after a while, a man knocked at my door, said, "Billy?" I said, "Yes." Said, "I hate to tell you this." I said, "But Brother Frank, I was right out there when she died." He said, "That's not it." Said, "Your baby is dying, also." I said, "Who, Billy?" Said, "No, Sharon." I said, "Surely not."

Said, "Dr. Adair has just come got her, and took her to the hospital, and she has tubercular meningitis. There's not a chance. They say she'll be dead in a little bit." She was perfectly healthy. I rushed just as fast as I could. They had to hold me, set me in a old Chevrolet truck, he and his boy. And I just couldn't hold myself together; my heart was breaking. Away to the hospital I went, went in. There set a nurse, said, "Now Reverend Branham, you can't go down in there. We got her in a isolated ward." Said, "You'll give Billy Paul the same thing." Said, "You can't go." I said, "I must see my baby."

She said, "You can't go, Reverend Branham; it's tubercular meningitis. She's picked it up from her mother. It's in the spine and she's dying now." And said, "If you go in there," said, "it's dangerous of taking it to the ba-... to your boy," and said, "You cannot go in." And she said, "Go in the room." And I went to the room. When she shut the door, I went right out behind the door and went right on down to where it was. Very poor hospital, I looked there, and they'd put a little rag over its eyes, little "mosquito bar," as we call it. Flies had got in its eyes. It was down in the basement in a isolated ward. I walked in and looked at my baby. There she laid, my sweetheart, her little teeny baby blue eyes looking up at me, her little leg, little fat leg laying there with her little corners on, you know. And she was... Her little leg was moving up and down like a little spasm, her little hand like it was waving to me. I said, "Sharon, you know Daddy?"

And her little lip started quivering. And she was suffering so hard till one of those little blue eyes crossed over like that. Oh, my. When I think of it... I can't stand to see a cross-eyed child. You know, sometimes God has to take a flower to crush it to bring the perfume out. I... Every time I see a cross-eyed child, I think of that. And I've never seen one yet but what God healed. Then I noticed that little eye moving over like that. I thought, "O God." I fell down on my face, I said, "God, please don't take her. O God, are You going to...?" I said, "Take me first. Let me die. I'm the one that's transgressed." But God knows just how to get at your heart. Yes, He does.

And I said, "I'm the one that's done wrong, Lord. Oh, don't take my baby. Take me, Lord. My wife laying yonder in the morgue, and here You're going to take my baby. Please don't do it, Lord. I--I've served You; I--I'm ashamed of myself that I listened to somebody instead of You. I'll never do it again, Lord. I--I'll live for You, I'll do all that You want me to do. Them people's not back-wash, they are not trash." I said, "I'll go. I don't care who's calls me holy-roller or whatever they might do it. I'll serve You if You'll just let my baby live, Lord. Please do," beggar like that.

And I looked down. And just as I looked down to where lay, here come a black sheet moving down. I knew that was it. I knew she was going. I looked over at her like that. And her little mouth begin coming open. Her eye was crossed over. And I said, "Sharry, you know Daddy, honey?" And she was making a little funny noise. And I laid my hand over on her head.

Then Satan moved to me, and said, "Will you trust Him now?" I laid my hand on her head, I said, "God, You gave her to me; You're taking her away from me. Blessed be the Name of the Lord." Said, "God, I can't deny You; I can't say that You are unjust. I duly deserve all this punishment. You're still just, and I still love You. I'll still serve You with all my heart. Now, to my baby, Lord, I've begged You; I have tried to get You to keep her, but nevertheless, not my will, let Your will be done."

Just then I felt my human strength giving away, my body crumbling down to the floor; I held on to the side of the bed. And the Angels of God come and got her little soul and packed her to her mother. I took her little body, laid it on the arm of the mother; there I looked there, and oh, my. Took her out to the graveyard, lowered her down. And Brother Smith standing there, the Methodist preacher, preached her funeral, put his arms around me, picked up the clods of dust, sprinkled it upon the casket, said, "Ashes to ashes, dust to dust, and earth to earth." My heart went down in there, too: my sweetheart, my baby. Then Billy Paul took sick. He was laying right at the point of death, eighteen-months-old. Last time he seen his mother (standing, my old baseball cap on, out in the yard, like that), and her going down in the ambulance, her boney hand, waving, saying, "My baby. My baby." Little fellow standing in the yard... I know... Excuse me. She... When you going down the street, and Billy was at my mother's house, and he was looking at her, didn't know in there went his mother, going right to her death; and her trying to wave through the ambulance window at her baby there in the yard; poor little fellow.

I looked down. They buried her. It seemed like come whispering down through those trees, seemed like I could hear a voice say: There's a Land beyond the river, That they call the sweet forever, We only reach that shore by faith decree; One by one we gain the portal, There to dwell with the immortal, Someday they will ring those golden bells for you and me.

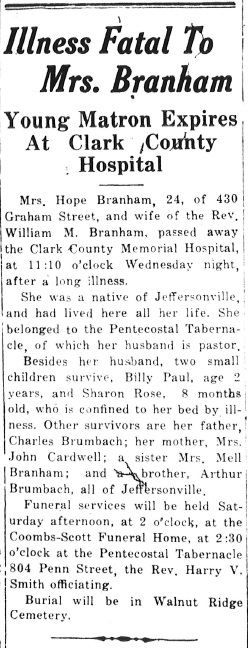

While performing our research on the Municipal Bridge Vision, we ran across Hope’s obituary in the Jeffersonville Evening News:

We were quite shocked when we saw this line in her obituary:

“She belonged to the Pentecostal Tabernacle, of which her husband is pastor.”

Brother Branham’s error was being introduced to Pentecostal “Holy Rollers” in Mishawaka and refusing to be associated with them and go out amongst them. He said he was a Missionary Baptist, and knew nothing about Pentecost. Why then, was his church named the Pentecostal Tabernacle before Hope died?

We couldn’t reconcile this with Brother Branham’s life story or with the stories we’d been told by other believers. We started to get the impression that perhaps Brother Branham was a Pentecostal prior to Hope’s death in 1937. We began to look at this topic further and try to determine through primary reference sources when Brother Branham was introduced to Pentecostal people and when his church was named the Pentecostal Tabernacle. We’ve decided to share what we’ve discovered in our upcoming posts.

blog comments powered by Disqus